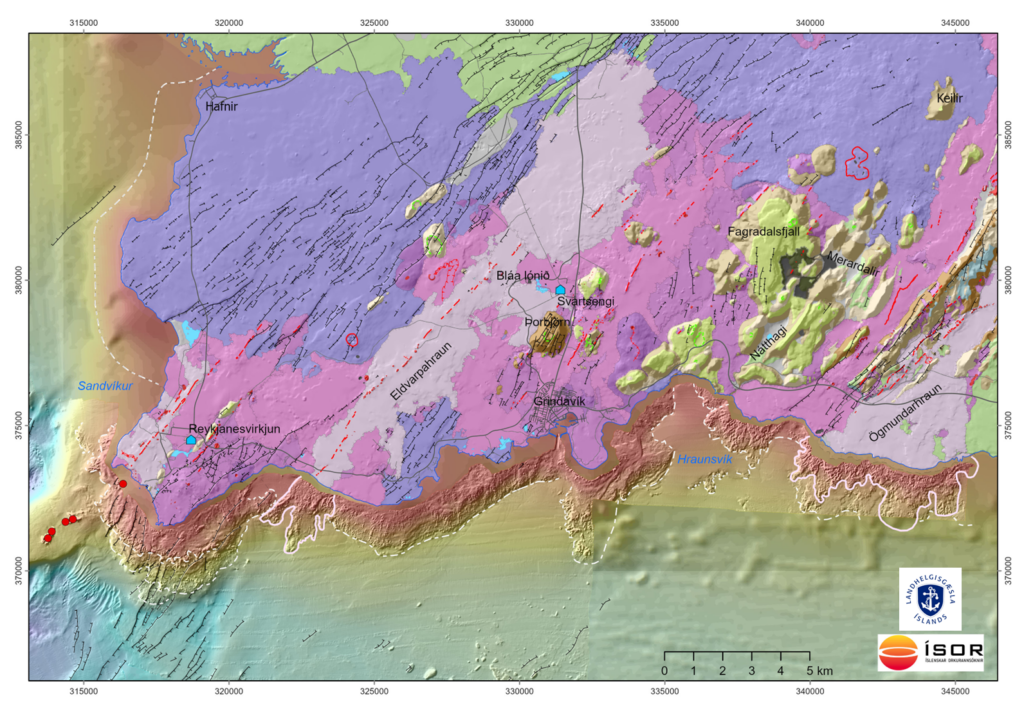

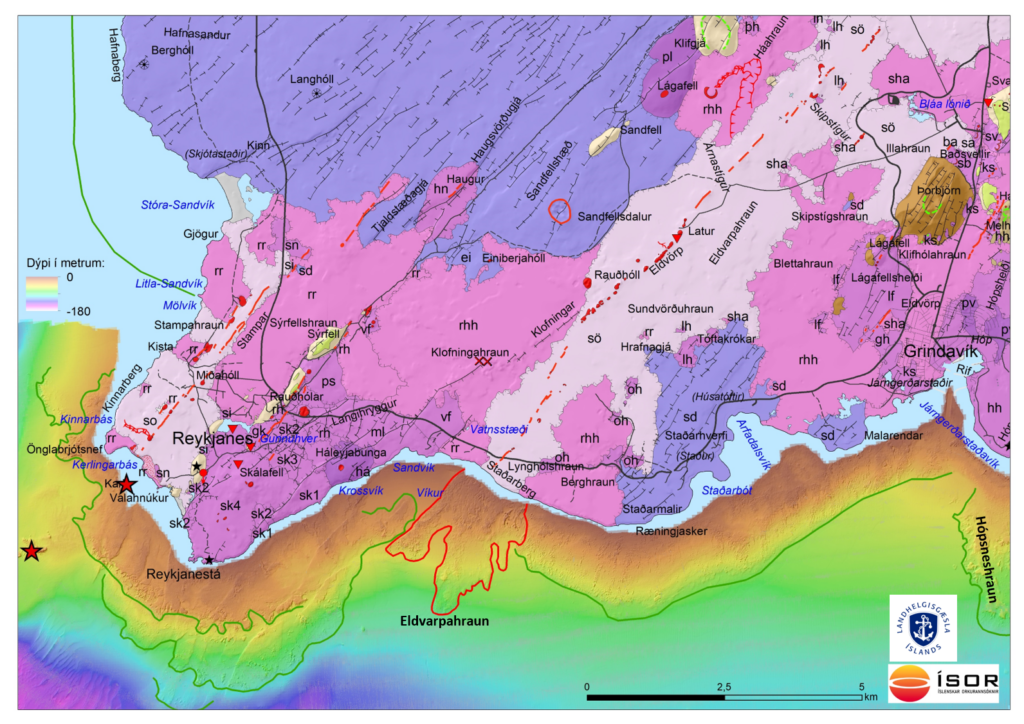

In light of the events at Grindavík, south west Iceland, in recent days and weeks, there is reason to review ÍSOR’s coverage from February 2020 about lava flow into the sea and submarine eruptios in historical times in the Grindavík area. The events called the Reykjanes Fires (Reykjaneseldar) took place by repeated volcanic unrest between 1210-1240, about 800 years ago, resulting in submarine eruption off Reykjanes and lava flows on land both at Reykjanes and at Svartsengi. One of these lavas was Eldvarpahraun located west of Grindavík. The row of craters that erupted then, called Eldvörp, is over 8 km long and extends from Svartsengi all the way to the south coast at Staðarberg, where lava flowed into the sea.

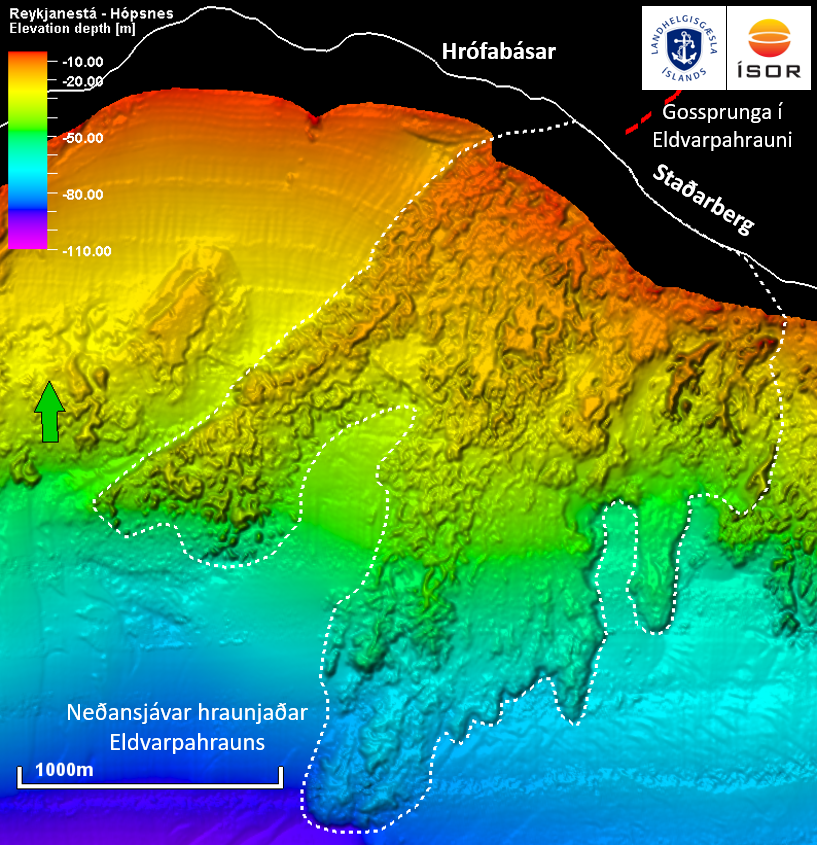

Multibeam data obtained by the Coast Guard of Iceland was processed by ÍSOR and shows clearly that the lava didn‘t stop at the shore but flowed forward a long way underwater. The furthest point extends to about 2.7 km from the coast and to a depth of about 90 m. It is possible that the volcanic fissure itself also extended beyond the coastline and that there was an eruption on the sea floor at the same time. It is difficult to identify a submarine crater or craters, but the location of the lava rim on the seabed indicates lava flow through a fissure without much explosive activity. The area of the lava on the sea floor is about 3.4 km2.

This is by no means unique, the Hópsnes peninsula at Grindavík is made of lava that flowed towards the coast and formed a tang out into the sea. It is about 8000 years old and extends underwater to a depth of about 100 m.

ÍSOR’s seabed maps of Reykjaneshryggur and Kolbeinseyjarhryggur north of Icleand show lavas that have flowed across the seabed from craters and fissures at great depths. It is believed that these are socalled pillow lava sheets. In order to flow this way, the lava needs to somehow protect itself from oceanic cooling by forming an insulating mantle of cinder and solidified rock as they flow. It is clear that the flowrate has to be high and constant in order for a this lava to form and flow forward on the seabed. Under such conditions, it would likely be difficult to stop the lava flow by artificial sea cooling using pumps.